Introduction

At this time in history when it seems particularly difficult to keep women safe from violence and exploitation, it would be easy for feminists to despair. But I am always inspired when I remind myself that I am part of a long line of feminist warriors.

A feminist folksong from the 1970s “Woman River Flowing On” stands as a reminder that we are part of a larger movement of women running through time. Here I want us to draw on women’s history – on that Woman River – for inspiration for the struggle that is still before us.

This paper aims to examine the groundbreaking, often momentous and sometimes contentious insights offered by feminist thinkers into women’s oppression and, in particular, the issue of violence and consider their relevance in today’s world.

Since the turn of the century there have been rapid and massive changes. We have seen escalating globalisation which has connected and intertwined the lives of peoples across the world at the same time as it has entrenched and deepened inequalities. We have seen the rise of religious fundamentalisms - essentially political movements which use a selective version of the religion to attempt to win power and extend social control. And we have seen the ideology of militarism shape and influence world concerns, international relationships and domestic priorities. Each of these has major implications for women and women’s safety.

Such significant social change can create considerable ethical challenges and requires us to grapple with complex issues if we want to find fair and just responses, especially for women. I contend that our social institutions - government, education, the media - have not risen to this task. Governments are poll driven and tend to take the conservative stance. Academia conforms under threats of financial cuts and, with a few exceptions, the media is maniacally concerned with the “ten second grab” and the next new fad. Mass culture seems to be all about the "dumbing down" of the populace and a simplification of any ethical or moral stance. As global politics become more complex and ethical dilemmas more challenging we seem to crave simplistic explanations, safe answers.

And for those of us particularly concerned with the struggle for women’s rights these have proved to be difficult times. We are living in era where the sustained backlash against feminism and the fight for women’s equality has made a serious impact. Our popular culture presents an image of women as having choice and equality. Catharine MacKinnon says: "We're now in a stage where people want to believe that there is equality. They'd rather deny inequality than face it down …..." Catharine MacKinnon, Guardian article April 12, 2006 re book Are Women Human.

Words like patriarchy, exploitation and oppression are passé and quaint and talk of a struggle for liberation is often met with indifference, impatience or even veiled hostility.

If we object to pornographic images of women, we are castigated for denying freedom of speech.

If we object to violence and name this as an act against women by men, we are regaled with stories of how women are violent too.

If we protest the sexualisation of young women and girls through fashion, we are decried as denying them choice.

If we say prostitution is abuse and degradation of women, we are accused of discriminating against women who elect this as a means of earning a living.

These charges often render us publicly silent and privately confused. We have been so imbued with the tenets of freedom of speech and choice that distinctions between competing rights are hopelessly blurred or disallowed altogether.

So, those of us who think otherwise, who want to make the world fairer for women and who know there is much to be done - where do we turn?

I suggest that the voices of feminists over many years past have sounded some clear messages for us to consider today, messages that may help us make sense of our world and respond to accusations that would silence us. The insights of earlier feminists may require some re-interpretation or even re-wording to fit the realities of our fast-changing world, but they remain worthy of careful and serious consideration. I propose to explore examples of feminist thinking and revisit the wisdoms and warnings of our feminist foremothers so that we can assess their relevance to our continuing struggle to secure the safety of women as a basic right.

Wisdoms and Warnings

I have loosely grouped these insights, musings and declarations into a number of themes:

“The Personal is Political”

The invisibility of women’s lives and experiences, and the gap between the private reality and the public presentation has long been a cornerstone of feminist thought. Betty Friedan, in 1963, called this “the problem that has no name” and thus began the development of the idea that the knowledge which becomes public and is legitimated in a male dominated society, is the knowledge of men.

If human beings make sense of the world according to the information available to them, then when that information is filtered through male-controlled institutions, it is little wonder that prevailing views favour a male perspective. Being able to generate, validate and control our own knowledge about ourselves is then crucial for women.

This aspect of women’s oppression – male control of information which shapes society’s understanding of women and our understanding of ourselves – has been referred to by many feminists as the colonization of women’s minds.

Matilda Joslyn Gage, in the 1890s, urged women to break the mindset facilitated by patriarchy, to discover and express their own strength, to take over and control agencies of information which could reflect women’s experiences.1

Before her was Frances Wright (1795 – 1852) who urged women to break their mental chains2 and earlier still was “Sophia, a person of quality”, a French women, who in 1739 declared that so bold a tenet as that of male superiority ought to have better proofs to support it than the bare word of the males who advance it, for as they are parties with so much to gain if their word is believed, this must render their case highly suspect. Sophia too urged women to cast aside their mental bondage and to generate their own truths of their own existence…3

So, when Betty Friedan raised the issue of women’s discontent and the difference between their private lives and the version of their lives that was publicly represented she was tapping into a consciousness that had gone before.

“Women live in occupied territory”

In the 1970s, writers such as Kate Millett and Germaine Greer were also concerned with how women’s lives were presented publicly but they focused more on the distortions rather than merely on what was left out. Writing at the beginning of the heady period we now refer to as second wave feminism, they took an uncompromising stand on unmasking male power.

Germaine Greer, in her ground breaking book “The Female Eunuch”, states baldly “Women have little idea how much men hate them” and goes on to document chilling accounts of rape and sexual harassment. She contended that “rape is an act of murderous aggression which is enacted upon the hated ‘other’ with the intention of humiliating and degrading.”

In their analysis of male violence against women, both Kate Millett and Germaine Greer focus on the area where consciousness and physical reality meet and are keenly aware that women’s oppression has taken both emotional and physical forms. They and many others since have helped us to understand the way male power can be used as a threat to intimidate and control women.4

As Marilyn French put it “As long as some men use physical force to subjugate females, all men need not. The knowledge that some men do suffices to threaten all women.” (The War Against Women, Penguin, 1992, p184).

- The War Against Women

Many theorists and activists have pursued the concept of a systematic and sustained assault on women and have described the treatment metered out to women across the centuries and across the globe. It makes for harrowing reading. They identified a War Against Women and presented the concept of violence as a political act rather than merely individual aberration. From Mary Daly (Gyn/Ecology) to Susan Brownmiller (Against Our Will) to Marilyn French (the War Against Women) feminist thinkers have drawn out the politics of this violence and the way it is used to control women and reinforce patriarchal power. We can only wish it were otherwise.______________________________________________________

1 Feminist Theorists: Three centuries of women’s intellectual traditions, Dale Spender, The Women’s Press, London,1983, p 370

2 ibid

3 ibid

4 ibid (pp373-374)

Looking at the ways violence against women is infused in our culture, other feminist theorists point to particular practices.

Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin (“Pornography and Civil Rights” 1989) showed us how pornography and prostitution are used to fuel a culture of oppression and degradation of women – a culture which supports rape.Robin Morgan proclaims “Pornography is the theory and rape the practice” (The Word of a Woman p89)

Expanding on this, Susan Brownmiller wrote “Once we accept as basic truth that rape is not a crime of irrational, impulsive, uncontrollable lust, but is a deliberate, hostile, violent act of degradation and possession on the part of the would-be conqueror, designed to intimidate and inspire fear, we must look toward those elements in our culture that promote …. these attitudes, which offer men, and in particular, impressionable, adolescent males… encouragement to commit acts of aggression without awareness, for the most part, that they have committed a punishable crime, let alone a moral wrong.”

“(It) is inculcated in young boys … that being male means access to certain…privileges, including the right to buy a woman’s body. When young men learn that females may be bought for a price…..then how should they not also conclude that that which can be bought may also be taken …” (p439)

- Women in War

It would come as no surprise to note that these same theorists have written not only on the war against women but also about the treatment of women in war and that they name rape as a weapon of war.Catharine MacKinnon maintains that “Wartime is exceptional in that the atrocities by soldiers against civilians are always essentially state acts. But men do in war what they do in peace.” (p148). She goes on to say “Resort to arms inflicts disproportionate casualties on women and children, but so does the present peace.” and “If violence is an episodic eruption of men fighting other men, something that begins and ends, then peace becomes a period in which this is not happening. Male violence against women is tolerated in both… How will male violence ever end when the very idea of peace presumes and permits it?” (p278)

“No woman will be free until all women are free”

A common thread through these insights is the focus on understanding and analyzing power and the clear location of feminism as a political position. The struggle for women’s equality has never been about the advancement of individual women, but of women-as-a-group - the collective Women. Not only can women only attain change by working collectively but, to be effective, the benefits achieved have to be available to all.

Catharine MacKinnon, reflects this focus on the collective and the interconnectedness of women’s condition when she says that “women’s world is the globe. As women in one country achieve more equality, men seek out women with fewer options elsewhere – a pattern observable sexually in sex trafficking, sex tourism and mail-order brides and economically in labor trafficking, international outsourcing to sweatshops …. No more than clean air can women’s equality be successfully achieved in one country. No woman will be free until all women are free. (Are Women Human? Harvard University Press, 2006, p13)

* * * * * *

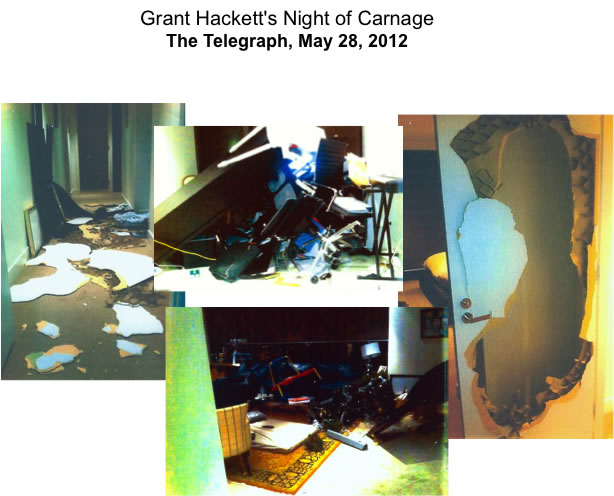

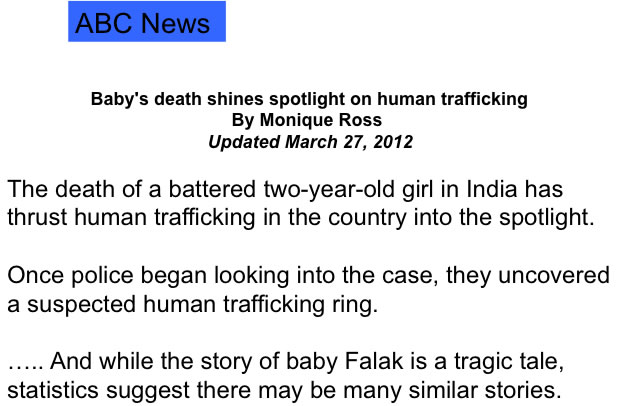

I would contend that these perspectives and many more like them from feminists across the world, are achingly, shockingly relevant to us in the 21st Century. With the technology now available to us we have daily proof of the continuing injustices done to women – because they are women, and we know the struggle is still before us. Here are a just few recent examples… (go to screen show).

The wisdoms and warnings offered by our feminist foremothers can inform us.

We need to remember that the personal is political and this means that women’s experiences and perspectives must be prioritised in our minds. We must use a women-centred lens when we look at what is happening in our world and be prepared to challenge the male mindset that is both dished out to us and that lives within our own head.

That our governments, media, educational and religious institutions fail to address key women’s issues, will come as no surprise when we remember the warnings of our feminist foremothers about who controls those institutions.

We need to understand that we live in occupied territory and acts of discrimination, containment and violence against women are not random individual aberrations but are targeted and systemic and are a part of maintaining masculine power and privilege.

And, probably most importantly, we need to know that no woman will be free until all women are free. While individual women’s experiences are important, feminism is about prioritising the safety and well-being of all women - improving the lot of the collective Women. This political position means that that which harms women is to be opposed.

So, the right of women to avoid harm can legitimately take precedence over the rights of the pornographers to their “freedom of speech”, and also over the rights of individual women to “choose” prostitution or pornography.

Through history, there have been periodic uprisings of women and new understandings of women’s situation are created. These uprisings are followed by a backlash – a counter-assault on women’s advancement. Much of that movement’s history, writing and thinking are lost and each new wave must start again. I say, not this time. Let’s make sure we don’t loose the strong, insightful and rigorous analyses of our foremothers. We might want to find new words for patriarchy, oppression, liberation – words that mean the same but better fit a 21st Century consciousness – but the wisdoms and warnings they convey are our legacy and are valuable tools for our future work. And if sometimes that work seems hard and the road long, let me leave you with the words of Indian activist Arundhati Roy.

"Another world is not only possible, she's on her way... On a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing".

Arundhati Roy speech she made in 2002, called "Come September".

References

Susan Brownmiller

Against Our Will; Men, Women and Rape, Bantam Books, New York 1975Susan Faludi

Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women, Chatto & Windus, London, 1991Marilyn French

The War Against Women, Ballantine Books, New York, 1992Germaine Greer

The Female Eunuch, Paladin, London, 1070Catharine A. MacKinnon

Are Women human? And Other International Dialogues, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, US and London, UK, 2006Robin Morgan

The Word of a Woman, Virago Press, London, 1993Arundhati Roy

Come September, Speech delivered in 2002Dale Spender

Feminist Theorists: Three centuries of women’s intellectual traditions, The Women’s Press, London,1983